In CNC machining, the rotation direction of the milling cutter is generally unchanged, but the feed direction is changed. There are two common phenomena in milling: down milling and up milling.

Milling cutter cutting edges are subjected to shock loads on every plunge. For successful milling, consideration must be given to the correct contact between the cutting edge and the material as the cutting edge enters and exits in a single cut. During the milling process, the workpiece is fed in the same or opposite direction as the milling cutter rotates, which affects the cutting in, out and whether to use climb or up milling.

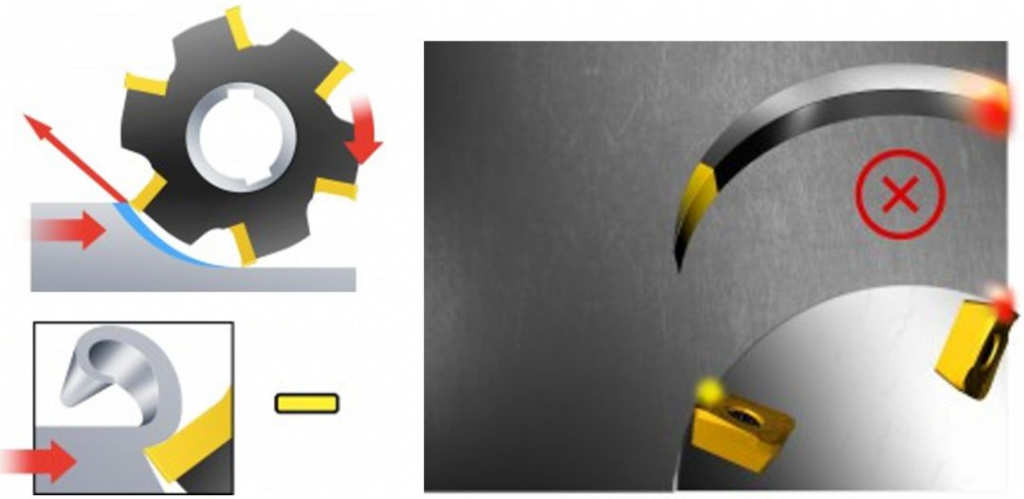

01 The golden rule of milling - from thick to thin

When milling, chip formation must be considered. The determining factor for chip formation is the position of the milling cutter, it is important to aim for thick chips when the cutting edge cuts in and thin chips when the cutting edge cuts out to ensure a stable milling process. Remember the golden rule of milling “thick to thin” to ensure the edge comes out with the smallest possible chip thickness.(ALL ALUMINUM CLASS A AMPLIFIER CHASSIS HOUSE)

02 Climb milling

In climb milling, the cutting tool is fed in the direction of rotation. Climb milling is always the preferred method as long as the machine, fixture and workpiece allow it.

In climb-edge milling, the chip thickness will gradually decrease from the start of the cut, eventually reaching zero at the end of the cut. This prevents the cutting edge from scratching and rubbing against the surface of the part before participating in the cut.(KNOB SUPPLIER)

Large chip thickness is beneficial, cutting forces tend to pull the workpiece into the cutter, keeping the cutting edge in cut. However, since the milling cutter tends to be pulled into the workpiece, the machine tool needs to deal with the table feed gap by eliminating backlash. If the milling cutter is pulled into the workpiece, the feed will increase unexpectedly, potentially resulting in excessive chip thickness and breakage of the cutting edge. In these cases, consider up-cut milling.

03 Up milling

In up-cut milling, the cutting tool is fed in the opposite direction of its rotation.

The chip thickness gradually increases from zero until the end of the cut. The cutting edge must be forced in, resulting in a scratching or polishing effect due to friction, high temperature, and constant contact with the work-hardened surface created by the front cutting edge. All of this reduces tool life.

Thick chips and higher temperatures as the edge cuts out will result in high tensile stress, which will shorten tool life and the cutting edge will usually fail quickly as a result. It can also cause chips to stick or weld to the cutting edge, which can then carry it to the start of the next cut, or cause the cutting edge to break down instantaneously. Cutting forces tend to push the cutter and workpiece away from each other, and radial forces tend to lift the workpiece from the table.

Up-cut milling can be beneficial when there are large variations in machining allowances. Up-cut milling is also recommended when machining superalloys with ceramic inserts, as ceramics are more sensitive to the shocks that occur when plunging into the workpiece.

04 Workholding Fixtures

The feed direction of the tool places different demands on the workpiece fixture. It should be able to resist lifting forces during up-milling. It should resist downforce during climb milling.